I don't know how one figures out what is right without looking at data. Introspection only gets one so far and introspection is really built to some extent on our relationship with data (at least broadly defined) at some point in our lives. I agree that a healthy sense of skepticism is necessary regarding empirical work, but Russell Robert's

recent discussions went beyond that.

Russell Roberts makes a pretty disappointing claim

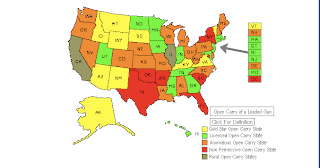

here that empirical data really only demonstrates the researcher's prior beliefs. Roberts then cites work on concealed handguns and lojack devices as evidence for his claim. Even more interesting, he references Ed Leamer (a former professor of mine) whose work has largely been set up to take out some of researcher's biases from the research that they present. Roberts fails to note that in More Guns, Less Crime I used Leamer's approach for both the sensitivity of specifications as well as bounding measurement error. As an aside, I also think that it is important that people share their data as an important check on the quality of research, even if others do not behave

similarly.

Unfortunately, Russell isn't familiar with much of the debate over concealed handgun laws. I think that the refereed academic research on concealed handgun laws by economists has had an impact. For example, how many refereed academic papers by economists or criminologists claim that right-to-carry laws have statistically significantly raised accidental shootings, suicides, or violent crime rates? I know of none. If Roberts can point to one paper, he should do so. Even most of the relatively few papers that claim to find no statistically significant effects have most of their results showing a benefit from right-to-carry laws. For example, Black and Nagin's 1998 piece in the JLS shows that even after they elminate about 87 percent of the sample (dropping out counties with fewer than 100,000 people as well as Florida from the sample), there are still two violent crime rate categories (as well as overall violent crime that they don't report) that show a statistically drop after right-to-carry laws are adopted. Mark Duggan's paper in the JPE is a similar example. Once the admitted typos in his Table 11 are fixed, most of the estimates show a statistically significant drop in violent crime. All but one of the results for murder show a statistically significant drop. There is only one of the 30 coefficient estimates that show a statistically significant increase, and even that is because he is looking at just the before and after averages and not trends.

My question is this: before this research, how many academics would have believed that at least some refereed research would show that right to carry laws did not increase accidents, suicides, or violent crime rates? I think that most would believe that some would find these results.

Robin Hanson gets to the central question: What Roberts would use to make decisions if he isn't going to use empirical work?

Try saying this out loud: "Neither the data nor theory I've come across much explain why I believe this conclusion, relative to my random whim, inherited personality, and early culture and indoctrination, and I have no good reasons to think these are much correlated with truth."Russell tries to respond

here. In particular he states:

Where does that leave us? Economists should do empirical work, empirical work that is insulated as much as possible from confirmation bias, empirical work that isn’t subject to the malfeasance of running thousands of regressions until the data screams Uncle. And empirical work where it’s reasonable to assume that all the relevant variables have been controlled for. And let’s not pretend we’re doing science when we’re not.Anyone can make such broad claims and many frequently have. Be specific. You have gotten into a debate over particular laws. What is it that you think should have been done regarding right-to-carry laws? What should have been controlled for that wasn't? What combination of control variables should have analyzed that wasn't?

Footnote: In Duggan's main estimates in the above discussed paper, it is interesting that the magazine he uses in much of his paper, Guns & Ammo, is the only one that shows the effect that he claims and that is because the magazine bought many copies of its issues in increasing crime areas (places where it thought there was a demand for defensive guns) when sales failed to meet promises to advertisers.

Labels: ConcealedCarry, Research